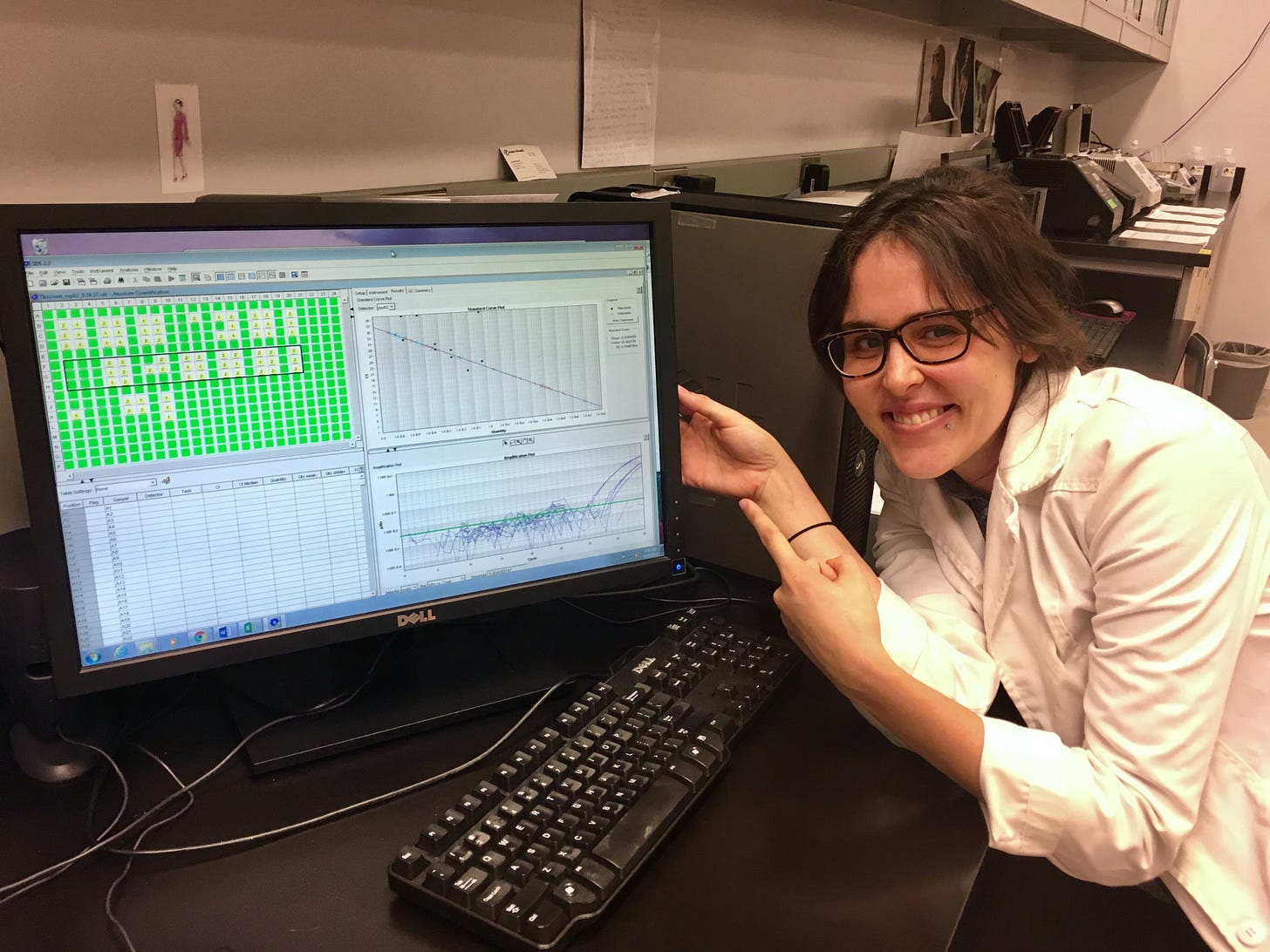

"Plotting a data set for the first time is like unwrapping the most delicious gift"

Job Shadowing #1: an archaeologist and geneticist

Welcome to Following Studies — an adventure through subcultures, obsessions, the things we follow & the things that follow us.

I love hearing about people’s jobs. We spend, usually, at least 40 hours of time at them, sloughing away for capitalism. Work is… fascinating. It’s complicated, it’s interesting, it can be incredibly boring. Give me a peek behind the curtain! That is what I want! I have a thing about employment. I want to know all about it. For a year of my life, I took high school and college kids to job shadowings and for other years, I helped people find employment. Even now, I write resumes for people when they ask.

I want to know about the ways we spend our time in this world. I want to unpack how so much of our identities are tied up in our jobs. What’s our worth? It’s not what’s on our paycheck but the world will sometimes make you feel like it is.

You’ll be getting a job shadowing in your inbox (hopefully) once a month and I’m excited. We can ask all the things we want to know about other people’s jobs — are you happy with your work? Would you have done something different? What does your actual day look like? We’ll talk about what we do, why we do it, what relationship we have with work and how the cadence of that impacts our personal worlds. What are we supposed to do with this one wild and precious life? Heck if I know. But let’s chat about it.

-Laura

P.S. Want to be featured in an upcoming job shadowing? Let me know!

Your Name: Dr. Kelly Elaine Blevins

Job Title: Wellcome Trust Early Career Fellow

Your Degrees:

BS in Biological Anthropology (Appalachian State University)

MSc in Paleopathology (Durham University, UK)

PhD in Anthropology (Arizona State University, Arizona, USA)

Laura: When describing your job at a dinner party, what do you tell people you do? What are you studying?

Dr. Kelly Elaine Blevins: At parties I use my hands a lot and enthusiastically tell people something like:

“I am an archaeologist and a geneticist, and I try to understand what people got up to in the past using their skeletons, the stuff they left behind, and their DNA, as well as their pathogen’s DNA. Right now, I am working on a project trying to understand how people who created the first agricultural villages in Southwest Asia about 10,000 years ago were related to previous populations of hunter gatherers. The triangular region formed by modern day Israel, central Turkey, and the Zagros mountains of Iraq and Iran had genetically distinct populations of hunter gatherer populations around 15,000 years ago, meaning that they were not interbreeding with each other. Our data are showing that all of these populations were coming together in the northern Levant (modern day northern Syria) and living and admixing (having sex with each other) and uniting under a homogenous culture. Was immigration responsible for the intensification and spread of agriculture, one of humanity’s most significant technological achievements? Maybe!

I am also interested in the social determinants of disease. I am starting a project that I developed myself to track how human social organization, hierarchy, and inequality - as we can see it in the archaeological record - impacted Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence and adaptation in Britain. For example, today tuberculosis is a disease of inequality, and a country’s TB prevalence is best predicted by prevalence of malnourishment. The more people infected with a pathogen, the more opportunities that pathogen has to evolve and adapt. So, I am attempting to link periods of peak social inequality - such as Roman enslavement, medieval poverty, industrial slums - to increased infectivity and virulence in M. tuberculosis by studying skeletons and recovering ancient pathogen genomes from them.”

L: Walk me through a day.

My days vary a lot. I have several different moods. Sometimes I am excited to work and can focus well, and sometimes I wake up and know I will be frustrated and cognitively slow if I try to work, so I just take the day off to rest. Other days I hyperfocus and code until 9pm. Therapy has helped me come to terms with these highs and lows and accept that my “successful academic” looks different from other “successful academics”. When I work from home I sleep until I want to wake up, usually not past 9:30. I split 1.2 liters of black coffee with my partner, who is also an academic. I make a big breakfast of last night’s leftovers. When I’m nice and amped up and jittery from coffee, I eat at my desk and dive into whatever the day’s task is - write an abstract, read papers to help formulate hypotheses and contextualize data, code analysis pipelines to summarize and get results from my genomic data, edit photos, write lectures, create practical exercises for students, write grant proposals, create grant budgets, order reagents, meet with lab supply representatives, present results at meetings, submit expense reports, write a manuscript, create a poster, plot data, or teach myself a new statistical technique. I eat lunch quickly and at my desk, usually while watching a YouTube video about whatever concept/topic I am trying to understand or integrate into my writing that day. I stop work when I lose interest or get tired or when I have finished something due the following day.

L: Can you share with us your academic journey starting at Appalachian State University? Was it always your goal to stay in academia?

My original goal was to go to med school and be a surgeon, because I was attracted to the intensity, urgency, and purpose of that profession (I identify as a Cristina Yang). I started undergrad as a chemistry major. While taking my pre-med biology requirement, I became interested in human evolution and wanted to learn more (it’s not taught in high school where I’m from, Newnan, Georgia). I took a biological anthropology course and learned about archaeology, and I was hooked. I changed my chemistry major to a chemistry minor and got a BSc in Biological Anthropology. I was captivated by the revolutionary spirit of archaeology: the way things are is not the way they used to be, so it's not the way they must be. I had still intended to go to med school but became increasingly obsessed with the reality of studying the past through the medium of the skeletons who lived it. During senior year I applied to do a MS in Paleopathology (the study of ancient disease) and said my final goodbye to a childhood dream of becoming a medical doctor.

I moved to Durham, England a month after graduating from App State and started an intensive 1-year masters course. I became excellent at human skeletal anatomy and identifying diseases on human bones, and I began learning about the intense satisfaction and rush of scientific discovery. The following summer I moved to Coimbra, Portugal for a month to look at skeletons from the 1900s with documented causes of death to try to determine if people who died of tuberculosis had more skeletal markers of childhood illness and stress, as opposed to people who died of accidental or non-infectious causes. The answer was no, they did not.

I moved back to my mom’s house with a £500 award for the best masters thesis in archaeology and a deep disappointment in the low resolution of skeletal data. I turned my gaze to ancient DNA, which was gaining traction at the time as the SEXY NEW WAY of studying the past. Unfortunately, I had no genetics training. This would crush my spirit today, but at the time I had so much more hope and energy, so I decided I would do a PhD in ancient DNA. I spent a couple months aggressively studying for the GRE. I memorized the definition of every GRE word. I took the test and did well in verbal and writing, but yikes my quantitative reasoning was low. Oh well, probably good enough I said. At this point I was living with Mom and broke (I spent all my thesis award money paying for the goddamn GRE!), so I got a job as a cashier at Target and began drafting all my PhD application materials. I narrowed down my list of schools, I emailed potential advisors, and I spent my lunch breaks at Target writing and editing my personal statements. By December 2015, I had applied to three PhD programs. By April 2016 I had been accepted by one and rejected by two.

A funded PhD position! I was on top of the world! Then I moved to Arizona and started that PhD. I spent two years trying to learn everything I could about genetics and genomics through coursework, seminars, and journal clubs. I worked weekends and nights, and I drank a lot of alcohol. I took full course loads and left the lab at midnight sometimes. I had a 4.0, and every day I taught myself something new. I won a Fulbright fellowship to study tuberculosis in the Mexica (Aztec) empire, this time using ancient DNA. No one ever told me I was doing a good job. Graduate school is deeply damaging. You work incredibly hard, you barely make minimum wage, you have no promise of getting a job once you finish, and the university treats you like a burden even though for the lab-based sciences your work enables professors to publish and bring in grants. It’s a crap pyramid scheme.

During the 5th and final year of my PhD at Arizona State University, I started applying to postdoc positions, because despite the angst, misery, and emotional trauma, I was addicted to the intense satisfaction and rush of scientific discovery. Discovering something - like what strain of tuberculosis someone had 500 years ago - that no one else knows is an incredible feeling. And I wasn’t and still am not ready to give that up. I accepted a postdoc, which is what a fixed-term contract to do research is called, in the Durham University Archaeology Department. After two years of my three-year contract flew by, I began applying for jobs and fellowships (grants that also pay your salary). I got job interviews, but no job offers. In the midnight hour, I was awarded a Wellcome Trust Early Career Award. It is everything. I am now well resourced, have semi job security, and the self confidence that comes from having a panel of 12 scientists listen to you speak and decide you’re worth £700,000 and ready to forge your own research trajectory.

L: In my day job, there is a normal cadence of work - months that are busier, others that are kinder and less stressful. How does your year flow? What are some rhythms you find?

I teach several courses in the spring, so my spring months have a bit more structure. Other than that, I am fortunate enough to be able to plan my work around my holidays. I do a lot of different things - lab work, writing, traveling to look at skeletons, coding. There isn’t a predictable rhythm so much as me just getting things done in order of urgency.

L: I’m curious about your research - what brought you to it? What keeps you interested?

Philosophically I am captivated by the revolutionary spirit of archaeology: the way things are is not the way they used to be, so it's not the way they must be. I love piecing together the past and learning about all the ways humans have experimented with cultural and social structures and religion. I find the evolution of pathogens very interesting, but I also think there is something useful to be learned from understanding the ways humans and pathogens have co-evolved and adapted to each other through time, which is what I aim to demonstrate. No doubt what keeps me interested is the discovery. Plotting a data set for the first time is like unwrapping the most delicious gift. It’s exhilarating, and there is also a humbling sense of responsibility. We are telling stories about the human past and experience, and it’s important we tell them correctly.

L: When I think of working in academia, I think research & teaching. Of course, nothing is ever that cut and dry. What are some hidden aspects of the field that you weren’t anticipating?

Administration and university bureaucracy can be extensive and exhausting. I also naively thought you could just do awesome research and that would be that, but no. Academia is a constant game of overselling yourself and ideas trying to convince funders to give you research money.

L: If you had been given some helpful career advice when you were just starting out, what do you think you would have needed to hear?

“If you can imagine doing anything else, do that thing. Academia will absolutely wreck your self-esteem, work-life balance, and finances. Graduate schools (at least in the US) operate on a model of student surplus - cheap labor for universities, because instead of hiring qualified permanent staff to generate data and teach, graduate students do it. There are so many more people with PhDs than there are academic positions, and that will not change any time soon. You have to be excellent to succeed through the bottleneck.”

I think only that bluntness would have sent me back to chemistry and med school.

L: What would be the one thing you would have to immediately replace in your working world (tangible or otherwise) if it broke?

My MacbookPro. Followed by my monitor and my French press.

Thank you, Dr. Kelly Elaine Blevins! Read some of her research here.

Tell me in the comments — what’s your relationship with your job?