In preschool she worked in her parents' drug operation

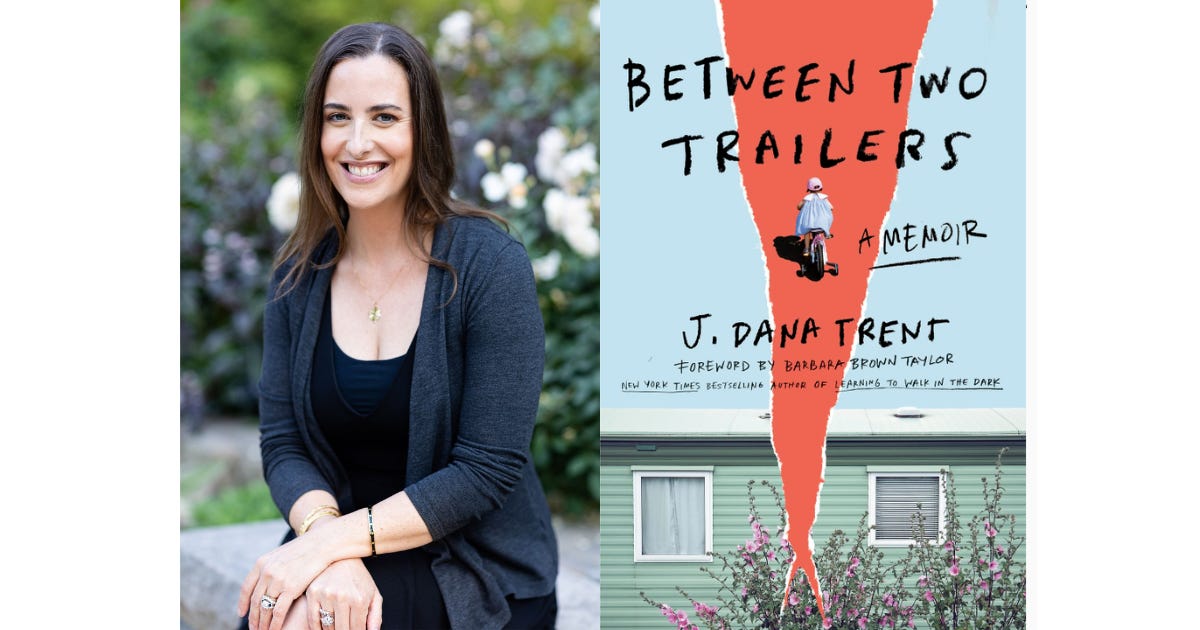

Read J. Dana Trent's memoir, Between Two Trailers, out today.

Welcome to Following Studies — and adventure through subcultures, obsessions, and the things that bring people together. I’m glad you’re here. If you think someone else would have fun hanging out with us, be sure to share.

J. Dana Trent has been many things—a chaplain, a teacher, a writer, a YMCA fitness instructor—but she started her working life as a child when her parents noticed that her tiny preschool hands were perfect for welding razor blades to separate seeds and stems from the bud in her parents’ drug operation.

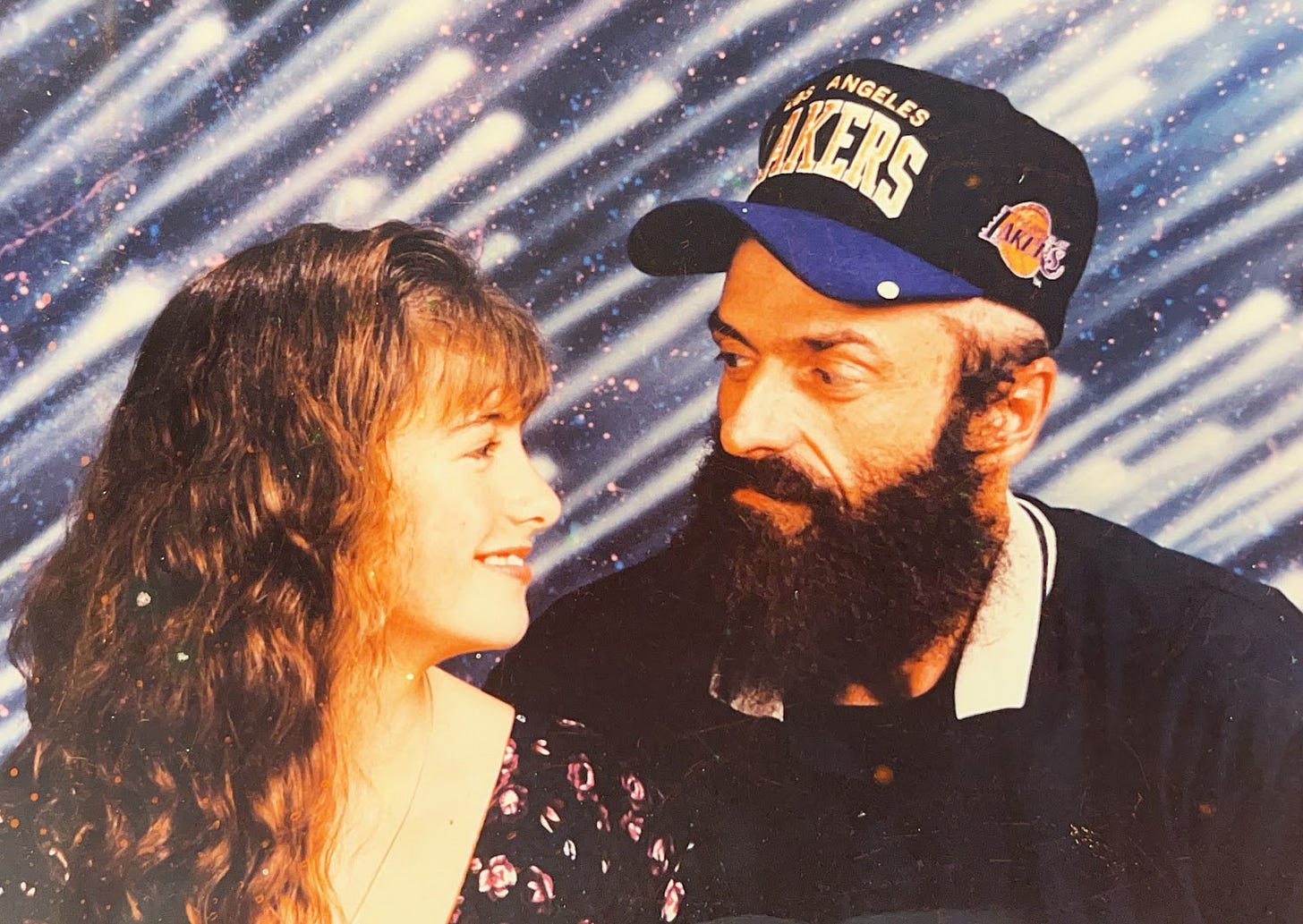

Dana’s parents, nicknamed King and The Lady, both experienced mental illness, and throughout Dana’s childhood, she dealt with the extreme stress and trauma of her home life — all of them ACES (Adverse Childhood Experiences). But in writing about her family, Dana takes us through a journey of finding her personal identity beyond her origin family so that she can have peace.

I remember meeting Dana years ago while writing a piece for IndyWeek, hearing about her childhood, and thinking my goodness; this should be a book.

Lucky for all of us, now it is. I caught up with Dana again to talk about her memoir (out today!), Between Two Trailers.

Laura Guidry: I remember so clearly sitting at a coffee shop years ago with you, hearing about your childhood, and thinking, you have got to write a book about this. You shared about your childhood in a podcast, and now you are releasing your memoir, but it’s not your first rodeo or book. I was curious when you knew it was time to share this story with the world.

J. Dana Trent: Well, the podcast was the easiest way to get in, right? Because I can be cerebral and generic. It was grant-funded. I was finding my way into this story, but under the auspices of being data-driven, like specifically looking at substance abuse, poverty, and mental illness in one county in Indiana - Vermillion County, where I grew up in these two trailers. And so the podcast was a launching pad. When everybody loved the podcast, and they were like we want more and more and more, I realized, okay, my parents are gone. I've done the data part, and now I've got to start shaking the mental Polaroids of what actually happened for me on a personal level in this nuclear family. So that was really the inciting incident. The podcast was getting sort of my feet wet and looking at a bird's eye view at this county and all of these huge issues, but still keeping it very safe and abstract and not really getting to the nitty-gritty of what actually happened in my life. So when folks were like, no, you got to do more, I started to find an agent and then write a book proposal for what would ultimately become Between Two Trailers.

LG: That's incredible. When I was reading the book, it was so interesting because in your early years, when you’re 3, 4, 5 years old, it’s very clear you're like, this is normal life — my life experience is what everybody else's life experience must be. When was the time that you realized that your upbringing was unusual?

JDT: I can pinpoint that exactly. It was 2017 in Collegeville, Minnesota. This was pre-podcast, and I was sitting around a table with religion journalists, and we were pitching ideas about religion stories. I sort of, off the cuff, said, yeah, you know, my father was a cult leader at Indiana State University. We were talking about new religious movements, and they were like, whoa, whoa, whoa - you know, back that up. So I started to describe teaching, and then I started to talk about drug trafficking and, marijuana specifically. And they're like, no, no, no, no, no. I had thought, oh, yeah, that was probably everybody probably grew up with — with a parent like this and kind of a larger-than-life parent, and my colleagues were like, no, not at all. Not at all. And I was 36. I was 36! That was in July of 2017. My mother died a month later. So that seed was planted in that writer’s workshop where I thought, wow, maybe it is time to tell this story that I really didn't think was a big deal.

LG: King was, I don't want to say, the perfect cult leader, but definitely a larger and like larger than life type of person. It was clear how much you loved him in the pages of this book, and it was so wonderful to read. There is that kind of strange juxtaposition of having a complicated family, but just the complications doesn't remove that familial love.

JDT: You know, families are universally complicated in different ways. And blessed are the complicated hearts. You can have love for family and still have division in family and estrangement in family. And I think for me, the going and getting back to admitting that this was my life and that it was unusual when also sort of always competing with this overarching desire not to reveal anything about myself and my Indiana upbringing because I was ashamed of it. I'm not even sure I knew how deeply that shame was rooted because it was mixed in with my mother. My mother had this fervent clingingness and desire for me to be her Carolina chaplain daughter and to surgically remove all the bits and pieces of any Indiana muscle and connective tissue from my personality, from my accent, from my culture or my family history to just make it so like my life started over when we moved to North Carolina when I was six. She wanted the rest of it null and void.

LG: That's so wild. I found that scene where you're talking about a psychiatric appointment so interesting in your memoir. It seemed like your mother had this significant desire to find a diagnosis within you, almost as if that would explain her difficulties with motherhood and raising you in more of a stable environment. We saw some of your ACES play out when you were in college and when you were first on your own — when you were almost coming out for air. Of course, when you were a child, the doctor told your mom you have significant trauma. You write about having suitcases of ACES. What was it like being a kid looking at her mom, who was also looking at her, saying: how are we similar?

JDT: Right, I had nothing at all, no sociopathy and schizophrenia. My mother was expecting personality disorders, but it was just straight-up PTSD, which we really didn't even talk about that much in the 80s. I think it was a projection, a transference, and that was lifelong. My mother was always the most helpful, loving, and supportive parent when I came to her with any kind of mental health symptom; that's when she showed the most affection she ever shared for me — if I were crying, anxious about school, depressed about a boy, distraught over failed friendships like the ones I had at Salem College. I think it was a misery-loving company, and I think it also fueled her innate desire to be a therapist. She was a psychiatric nurse who liked to play therapist on my dad and diagnose him as psychotic and then also play therapist with me and say, well, my daughter has sociopathic behavior or whatever. That was her gut instinct, which turned out not to be true. I also think that's an enmeshment — that's codependency. It's like classic textbook codependency. And an attempt to keep someone in the home with you. That was my mother's favorite thing to do because it made us and made me need her more. It was her M.O. of keeping me entangled with her. I do think you develop coping mechanisms inside your 0 to 18-year-old home. They work well, even if they're maladaptive. But then when the environment changes and you’re no longer living with these very toxic people, then your go-to tools go out the window, and they don't work— with your college roommates or your professors or people that are trying to get to know you as your own independent person. They just fall flat.

LG: I think it’s hilarious we both went to Salem College. I honestly had forgotten that, and when I got to the part in the book where you went to college, I thought, wow, what a subculture to dive into as you're coming up from air from your childhood, especially when you are going to a private school without private school finances. It felt like in your college experience, you were also having to kind of balance this line with your mom and classmates of what was normal and what wasn’t as far as her intrusiveness with you, particularly on campus.

JDT: You know, going full circle, that's kind of the way it was with King, although he was such a hidden figure. The truth was always triggering to my parents, so I couldn't draw a boundary. I couldn't tell them the truth about anything being embarrassing. I didn't even have the language to do that because I never did that. I never asserted myself. I didn't do that natural stage of development that all kiddos are supposed to do, which is to be defiant, to chart their own path, and to start separating from their parents to begin to discover who they are as people. I never had that. I had to normalize this behavior, which was really their mental illness. I did a lot of covering for them.

LG: Your childhood existed in two places. We have you in North Carolina, we have you in Indiana, but also, we have you between the instability that your parents gave you and the stability that other adult figures in your life would try to give you in moments. What was your experience of always existing between two things—especially when those two things were such extremes: the drug world and the religious southern world?

JDT: I have lived in my life as two disparate daughters, that they both vied for vehemently my entire adult life, and my mother really won out. You could argue that I've never really known who I am. And that came through in all my trauma responses — in all the fawning of being so fearful that my parents would leave me was this sort of ping pong or being in between them and just going back and forth, but never figuring out who I am. I’ve lost decades of my life. I guess that's one of the impetuses in writing this book. I can't leave the trauma to fester anymore because I'm losing. I'm losing myself. Originally, I thought this book was about them, and like that, that speaks exactly to your point, right? Of always bowing or genuflecting to both sides of the aisle but being unable to honor my true self. I thought this book was about them, but I think in the end, it's really about me trying to discover who I am, honoring that part of myself, and then drawing a line in the sand and saying, this is my story. This is what happened to me, and I'm going to do my best to integrate those parts of myself because I’m really both, I’m both of those people.

You can buy Between Two Trailers - out today!

J. Dana Trent spent years caught between two trailers — between her mother and her father and between Indiana and North Carolina. Has there been a time you’ve been caught between two places?

Oh wow, this was such a compelling interview! I’m so looking forward to reading the book

What an incredible story!